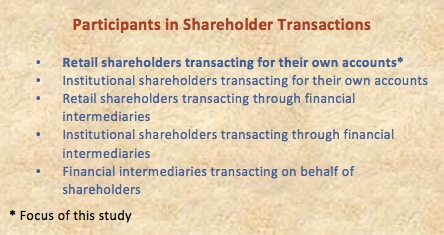

Broadly speaking, participants in transactions involving mutual fund shares can be grouped into three categories: (1) shareholders (both retail and institutional), transacting for their own accounts directly with fund groups; (2) shareholders (both retail and institutional), transacting through financial intermediaries (such as banks, broker-dealers, retirement plan recordkeepers, insurance companies, registered investment advisers, fund supermarkets); and (3) financial intermediaries, transacting on behalf of their omnibus clients.

In the past, many fund groups transacted directly, through internal or external transfer agents, with a significant percentage of their funds’ shareholders.1 In recent years, financial intermediaries have assumed a growing role in providing services, including transaction-related services, to fund shareholders.2 As fund shareholders increasingly engage in transactions through financial intermediaries, the day-to-day responsibility for authentication of these shareholders has shifted from fund groups themselves to the intermediaries. A detailed discussion of intermediary relationships between shareholders and fund groups is beyond the scope of this study. Readers seeking more information on these relationships may wish to consult the Investment Company Institute and Independent Directors Council’s paper, Navigating Intermediary Relationships.3

Notwithstanding the growing role of financial intermediaries, a significant number of fund groups (including many that are commonly viewed as relying on the intermediary channel) continue to transact directly, through internal or external transfer agents, with at least some portion of their funds’ shareholders. For these fund groups, implementation of appropriate shareholder authentication measures remains an important risk management issue. Indeed, even fund groups that do not transact directly with their funds’ shareholders should have an interest in authentication issues, as authentication failures by a financial intermediary may have reputational or other adverse impacts on fund groups themselves.

Sources

- The “direct channel” of mutual fund distribution may be defined in different ways. Some observers may refer to sales directly to a retail shareholder from a fund group, while others may include sales through fund supermarkets, broker-dealers, wrap accounts, and even defined contribution retirement plans. See LEE GREMILLION, MUTUAL FUND INDUSTRY HANDBOOK: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE FOR INVESTMENT PROFESSIONALS 187-89 (2005). Because this study focuses on the authentication measures taken by the fund groups themselves in interacting with retail shareholders, the narrower definition of “direct” distribution is of greater relevance to this study.

- See, e.g., INVESTMENT COMPANY INSTITUTE & INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS COUNCIL, NAVIGATING INTERMEDIARY RELATIONSHIPS (Sept. 2009), http://www.ici.org/pdf/ppr_09_nav_relationships.pdf; The Omnibus Revolution: Managing risk across an increasingly complex service model, Deloitte (2012), http://www.investorscoalition.com/sites/default/files/Deloitte%20Report%20on%20Omnibus%20Accounting%203-16-2012.pdf (noting the transformation of mutual fund shareholder servicing by the rise of intermediaries); NICSA Intermediary Discussion Forum, Effective Intermediary Governance: Evolving Best Practices (Sept. 2012), http://www.nicsa.org/downloads/White%20Papers/Effective%20Intermediary%20Governance%20Sept%2025%202012.pdf (noting that many fund groups report that “the preponderance of assets – 80% or 90% or more – are held in omnibus accounts”).

- INVESTMENT COMPANY INSTITUTE & INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS COUNCIL, NAVIGATING INTERMEDIARY RELATIONSHIPS (Sept. 2009), http://www.ici.org/pdf/ppr_09_nav_relationships.pdf.