The fund industry relies on shareholder authentication as a fundamental means of protecting transactional integrity. This part of the study reviews general authentication principles, and outlines some of the inherent limitations of particular authentication measures and of authentication generally.

Shareholder authentication involves testing the identity of a user through the use of one or more “factors,” each of which may be implemented through one or more specific means, or “measures.”

Shareholder authentication involves testing the identity of a user through the use of one or more “factors,” each of which may be implemented through one or more specific means, or “measures.”

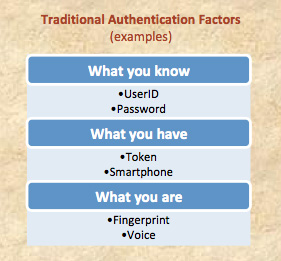

There are three “traditional” factors for testing user identities:

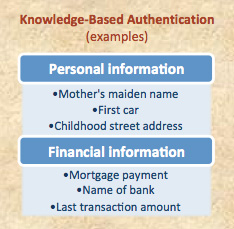

> The first traditional authentication factor, what you know , involves testing the identity of a user on the basis of something the user knows which is unique to that user. Reliance solely on this first authentication factor is generally referred to as single-factor authentication. One very common measure to implement this factor is to require a user to enter a username and password. Sometimes this factor may be implemented through use of additional measures, as well (e.g., asking knowledge-based authentication questions about a user’s personal life). The use of multiple measures (e.g., a username/password and knowledge-based questions) to implement this first factor is often referred to as enhanced authentication.

, involves testing the identity of a user on the basis of something the user knows which is unique to that user. Reliance solely on this first authentication factor is generally referred to as single-factor authentication. One very common measure to implement this factor is to require a user to enter a username and password. Sometimes this factor may be implemented through use of additional measures, as well (e.g., asking knowledge-based authentication questions about a user’s personal life). The use of multiple measures (e.g., a username/password and knowledge-based questions) to implement this first factor is often referred to as enhanced authentication.

> The second traditional authentication factor, what you have , involves testing the identity of a user on the basis of something unique that the user has in his or her possession (often a particular device). Measures used to implement this second factor may include issuing and requiring the use of a hardware identification token or smartphone. Reliance on both what a user has and what a user knows is often referred to as two-factor authentication.

, involves testing the identity of a user on the basis of something unique that the user has in his or her possession (often a particular device). Measures used to implement this second factor may include issuing and requiring the use of a hardware identification token or smartphone. Reliance on both what a user has and what a user knows is often referred to as two-factor authentication.

> The third authentication factor, what you are , involves testing the identity of a user using “biometrics” (i.e., a biological characteristic or attribute unique to the user). Measures used to implement this third factor may include establishing the identity of a user based on his or her voice, fingerprint, retinal or iris pattern, artery pattern, or DNA.

, involves testing the identity of a user using “biometrics” (i.e., a biological characteristic or attribute unique to the user). Measures used to implement this third factor may include establishing the identity of a user based on his or her voice, fingerprint, retinal or iris pattern, artery pattern, or DNA.

All else being equal, authentication systems relying on multi-factor authentication (i.e., the use of a combination of the first factor and one or both of the other two factors) are viewed as offering stronger protection than those relying on a single factor. Systems relying on all three of the factors are viewed as offering stronger protection than those relying on just two factors.

(i.e., the use of a combination of the first factor and one or both of the other two factors) are viewed as offering stronger protection than those relying on a single factor. Systems relying on all three of the factors are viewed as offering stronger protection than those relying on just two factors.

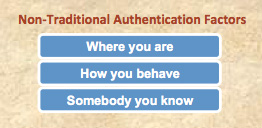

Certain current and/or proposed authentication measures may not always fit neatly within the framework of the three traditional factors. In order to categorize such measures, some experts have articulated additional, non-“traditional” authentication factors

Certain current and/or proposed authentication measures may not always fit neatly within the framework of the three traditional factors. In order to categorize such measures, some experts have articulated additional, non-“traditional” authentication factors . These include: (1) where you are (e.g., assessing where a user is located based on information provided by the user’s computer or mobile device); (2) how you behave (or what you do) (e.g., analyzing patterns of behavior with respect to logging in, navigating the website, or engaging in transactions); and (3) somebody you know (e.g., having your identity verified by one or more financial or other institutions).

. These include: (1) where you are (e.g., assessing where a user is located based on information provided by the user’s computer or mobile device); (2) how you behave (or what you do) (e.g., analyzing patterns of behavior with respect to logging in, navigating the website, or engaging in transactions); and (3) somebody you know (e.g., having your identity verified by one or more financial or other institutions).

Authentication is often viewed as primarily a one-way process, which focuses on testing the identity of a user. But authentication can also be a two-way process (i.e., mutual authentication ). Mutual authentication addresses concerns of users who may wish to have greater confidence that they are dealing with their financial institutions, and not with fraudsters. Examples of measures used in mutual authentication include the use of digital certificates and/or the use of images while logging into certain financial institution websites, with a caution to users not to proceed unless the images displayed are those that are pre-selected by users.

). Mutual authentication addresses concerns of users who may wish to have greater confidence that they are dealing with their financial institutions, and not with fraudsters. Examples of measures used in mutual authentication include the use of digital certificates and/or the use of images while logging into certain financial institution websites, with a caution to users not to proceed unless the images displayed are those that are pre-selected by users.

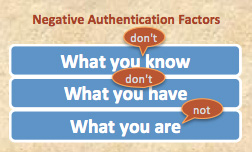

Authentication measures also may be referred to as “positive” or “negative.” Many authentication measures, including those relating to the three traditional authentication factors discussed above, are “positive” measures, in the sense that they are intended to positively identify a person seeking to effect a transaction as the shareholder (or other authorized person). Other authentication measures may be viewed as “negative,” in the sense that they are chiefly intended to screen out probable impostors. These negative authentication measures (or “de-authentication” measures) may be used to establish the identity of the person seeking to effect a transaction as somebody other than the shareholder. For example, a person’s ability to provide a shareholder’s Social Security number or address of record may not positively identify the person as the shareholder, but the inability to provide such basic information suggests that the person is an impostor.

Many authentication measures, including those relating to the three traditional authentication factors discussed above, are “positive” measures, in the sense that they are intended to positively identify a person seeking to effect a transaction as the shareholder (or other authorized person). Other authentication measures may be viewed as “negative,” in the sense that they are chiefly intended to screen out probable impostors. These negative authentication measures (or “de-authentication” measures) may be used to establish the identity of the person seeking to effect a transaction as somebody other than the shareholder. For example, a person’s ability to provide a shareholder’s Social Security number or address of record may not positively identify the person as the shareholder, but the inability to provide such basic information suggests that the person is an impostor.

Authentication measures have their limitations. Some of the authentication measures in common use by fund groups have become less effective over time. In particular, the single-factor username/password combination historically (and still commonly) used by fund groups to authenticate shareholders may, for various reasons, offer less absolute protection against fraud than it has in the past. A username/password combination (as well as other personal information) can be at risk of being lost or misappropriated (e.g., in the event of large-scale data breaches). Even absent misappropriation, fraudsters have become quicker and more sophisticated at cracking ever stronger passwords (including those with numbers, special characters, and a mix of capitalization).

by fund groups have become less effective over time. In particular, the single-factor username/password combination historically (and still commonly) used by fund groups to authenticate shareholders may, for various reasons, offer less absolute protection against fraud than it has in the past. A username/password combination (as well as other personal information) can be at risk of being lost or misappropriated (e.g., in the event of large-scale data breaches). Even absent misappropriation, fraudsters have become quicker and more sophisticated at cracking ever stronger passwords (including those with numbers, special characters, and a mix of capitalization).

Similarly, the information underlying knowledge-based authentication questions (e.g., a user’s mother’s maiden name or the name of a childhood pet) may be lost or misappropriated in large-scale data breaches. Even absent misappropriation, such questions may offer less absolute protection than in the past; with the rise of social media, such underlying knowledge-based information has tended to become more broadly available and accessible to fraudsters.

Authentication measures are subject to more general limitations as well. For example, the strength of a password—or, indeed, of stronger authentication measures—may be irrelevant if a fraudster compromises the systems of a financial institution and then causes such systems to transfer money or initiate transactions. Password strength is likewise irrelevant if a fraudster is otherwise able to circumvent the need for the password. For example, in a man-in-the-middle attack, a fraudster may “hijack” a session in which a user has already been authenticated by an organization. Because the fraudster is impersonating both the user (to the organization) and the organization (to the user), neither party may be aware that the session has been hijacked.

as well. For example, the strength of a password—or, indeed, of stronger authentication measures—may be irrelevant if a fraudster compromises the systems of a financial institution and then causes such systems to transfer money or initiate transactions. Password strength is likewise irrelevant if a fraudster is otherwise able to circumvent the need for the password. For example, in a man-in-the-middle attack, a fraudster may “hijack” a session in which a user has already been authenticated by an organization. Because the fraudster is impersonating both the user (to the organization) and the organization (to the user), neither party may be aware that the session has been hijacked.

Next