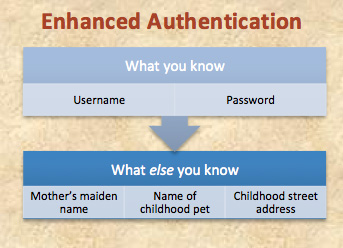

Reliance solely on the first traditional authentication factor, “what you know,” is often referred to as single-factor authentication, and most commonly requires the user to provide a username and password. In and of itself, the username has limited value in authenticating a user; rather, it serves to identify which user is being presented to a company for authentication.  The password is then used to authenticate that user’s identity. To enhance the effectiveness of the username/password combination, account lockout requirements (i.e., locking out a user from an account after a given number of failed login attempts) and/or password complexity requirements (e.g., minimum password lengths or the use of a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters) are frequently employed and enforced. Such requirements seek to strike a balance between password strength and user convenience. In the absence of complexity requirements, users employing self-selected passwords may gravitate toward weak passwords (with “password” and “123456” being among the most common in 20141). In contrast to user-selected passwords, automatically generated passwords are likely to have significantly greater “entropy” (i.e., the password is more random) and therefore afford stronger protection.2 Even so, requiring more complex passwords can sometimes be counterproductive—if passwords are too complex and/or are not self-selected by users, users tend to have difficulty remembering them, and, as a result, may resort to writing their passwords down and leaving them in plain sight.

The password is then used to authenticate that user’s identity. To enhance the effectiveness of the username/password combination, account lockout requirements (i.e., locking out a user from an account after a given number of failed login attempts) and/or password complexity requirements (e.g., minimum password lengths or the use of a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters) are frequently employed and enforced. Such requirements seek to strike a balance between password strength and user convenience. In the absence of complexity requirements, users employing self-selected passwords may gravitate toward weak passwords (with “password” and “123456” being among the most common in 20141). In contrast to user-selected passwords, automatically generated passwords are likely to have significantly greater “entropy” (i.e., the password is more random) and therefore afford stronger protection.2 Even so, requiring more complex passwords can sometimes be counterproductive—if passwords are too complex and/or are not self-selected by users, users tend to have difficulty remembering them, and, as a result, may resort to writing their passwords down and leaving them in plain sight.

Back